Tracking Change at Tokai Park

Reading Time: 7 minutes

Using remote-sensing to track changes in invasive alien trees at Tokai Park

By Matthew Collins

Matthew worked as an intern at Friends of Tokai Park (FOTP) for the month of August 2021 under the supervision of Dr Alanna Rebelo. Alanna, a member of FOTP’s committee, applied for funding for this work through WESSA’s small grants facility to cover this internship. Her time was donated as was that of Professor Tony Rebelo, who is acknowledged for supporting this internship with donated time in the field.

The aim of this internship was to explore change-detection methods for automating invasive alien tree mapping, as well as updating the alien tree map for 2021. It was also about capacity building and skills development for the candidate. The methods used were developed by Drs Petra Holden and Alanna Rebelo, as well as Glenn Moncrieff. This blog post is about Matthew’s internship, from his perspective.

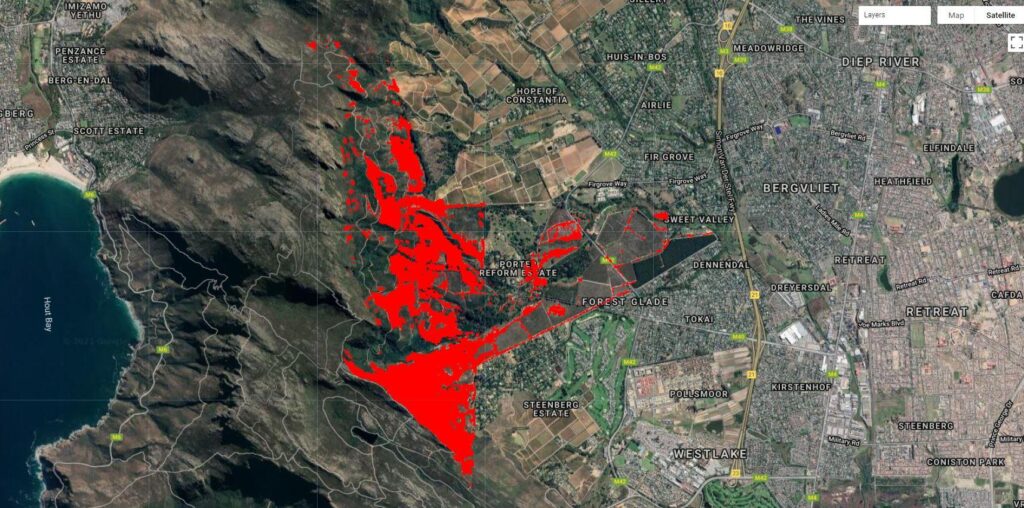

You probably recognise the above image of Tokai Park. If you live close by, no doubt you’ve enjoyed running, dog walking or cycling through and around it. Lower Tokai Park itself is large for a park, but if you include Upper Tokai Park it becomes even larger. Tracking changes in an area this size using traditional fieldwork methods (both in terms of plants and animals) is a massive task.

Satellite imagery, or remote sensing, is a relatively easy and inexpensive way to do this. All you need is an Internet connection and anyone can hop on to look at the state of their favourite area via satellite.

That’s where I come in.

Friends of Tokai Park took me on as an intern to help track changes in the park. With the help of a WESSA Small Grant, I spent the month using remote sensing to classify the Tokai Park area and monitor its vegetation – indigenous and alien.

The tasks given to me were the following:

- Use the method developed by Holden and Rebelo and applied to Tokai by Rebelo and the previous intern, Nicholas Coertze, to update the land cover types within Table Mountain National Park (fynbos, alien vegetation, water, rocks, etc.), with a view to producing a 2021 alien tree map.

- Apply Moncrieff’s method to Tokai Park to detect changes in alien trees over time.

In this blog entry, I’ll take you through the process of how we did this.

A bird’s eye view

First, I needed to familiarise myself with the region. Image 1 (above) is what the Tokai Park area looks like via satellite. It has some important features:

- One of the most recognisable is the dark pine tree plantation on the eastern side of the park, and then suburban housing to the north and south of that.

- To the far west lies the steep slope of Table Mountain National Park (TMNP). Invasive species still cover the steeper slopes, Working for Water (WfW) having not yet reached them.

- The area WfW has reached, the cleared area, is a brown/red colour and is accessible by road. It is not steep, rocky or dangerous to navigate.

- Then, in the centre of the image, is the more well-known part of Tokai Park, the area covered by the indigenous Fynbos we want to protect.

Remote sensing imagery displayed like this gives a great overview of the area. When combined with other instruments, it can be an effective tool for monitoring complex regions like Tokai Park as snapshots over time.

But, while someone familiar to the region might easily recognise the features I list above, this isn’t the case for everyone. I had visited the more well-known Lower Tokai Park but, before Professor Tony Rebelo gave me a tour, I hadn’t been to Upper Tokai Park.

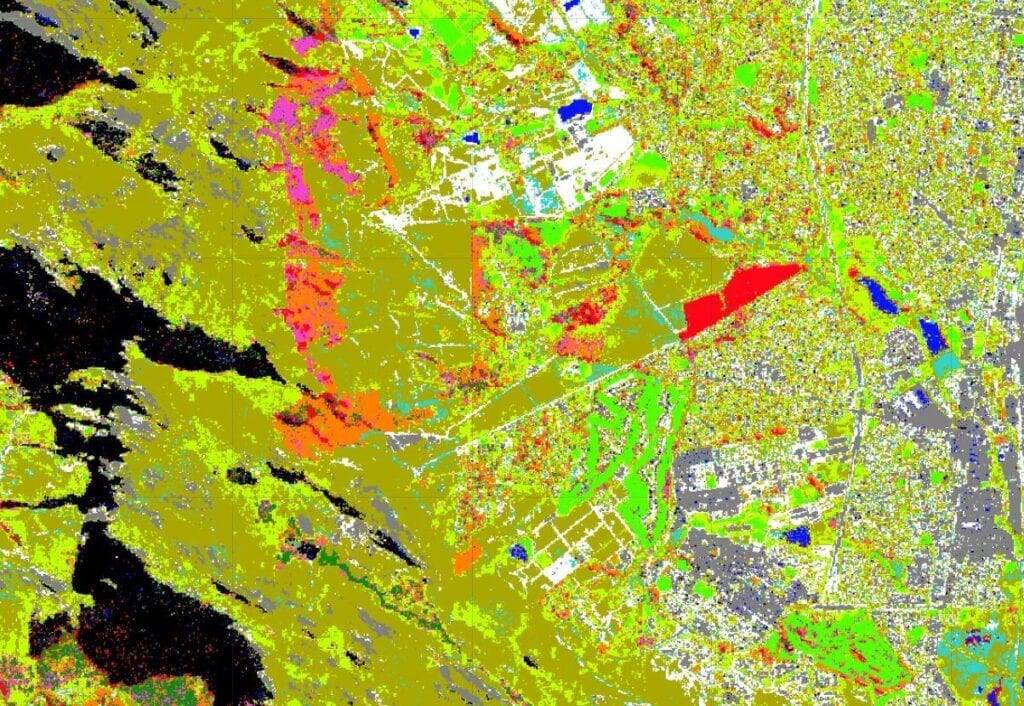

Classifying the region

Next, I classified the region into land cover types based on the methodology and code already developed by others. In the image above, different colours represent different land covers, including vegetation like: fynbos, wattle, and gum. If you’re unfamiliar with the area, images like this can make it easy to see the types of vegetation.

Still, it takes the trained eye of an ecologist to create these classifications in the first place. That’s why the tour to Upper Tokai with fynbos ecologist Professor Tony Rebelo was critical in helping me update the map for 2021. I learned how truly complex the region is, especially in Upper Tokai Park, where the aliens intermingle greatly, making it difficult to classify them (that’s why the pine, wattle, and gum are so mixed in the above image).

To recognise different alien vegetation, a view from the ground and the sky is needed to teach the algorithm what each land cover type looks like. The algorithm takes in a few hundred points per land cover type and then uses those examples to decide for itself how the rest of the area should be classified. Through this process, with the help of Alanna and Tony, I produced Image 2 (above).

Mapping change

Lastly, I was tasked with tracking how this area had changed over time. This makes it easy to see the progress Working for Water (WfW) and Friends of Tokai Park are making in clearing alien vegetation.

Some of these changes are normal variation. Untransformed areas change constantly because they’re covered with living vegetation, but some of them are the result of human intervention. We were trying to isolate these changes.

Alien clearing teams target alien vegetation in an area, clearing one ‘plot’ at a time. The focus of WfW in particular is currently on Upper Tokai Park, and they’re moving steadily uphill with each excursion. We can clearly see this: between July 2020 and 2021, changes are detectable.

In the above image, red represents areas that have been changed or cleared. As is shown, Wfw has already cleared a large area. However, there’s still a fair bit to go.

As the image shows, the upper slopes are untouched. This is because the terrain here is steep and difficult to manage. The roads further up have degraded badly, and travel is difficult for large teams with equipment. Additionally, the kloofs help protect and foster alien vegetation growth.

It’s important to note that this method is imperfect. The red masking doesn’t perfectly detect areas that have been cleared. For example, it incorrectly picks up dirt roads as areas that have been ‘cleared’.

Therefore, a probability map of alien tree clearing is better to use, which was the last task performed. The results are displayed below in a video of an application developed by Dr Alanna Rebelo. You can access this app on our Adopt-a-Plot page. Thank you to Alanna for also creating this video clip.

Image 4: The probability of change being detected correctly. The green shows a high probability, and the blue shows a low probability.

We can use this probability result to get a clearer understanding of the changes. The Alien Tree clearing Probability 2021 image is more complex, so it helps to compare it alongside satellite imagery.

From the result, we can see the following:

- The blue areas on the right show the pine plantation and the fynbos of Lower Tokai Park which remain unchanged since 2020.

- The red areas on the left, on the slopes of Upper Tokai Park, show where aliens used to be – much of this area has been cleared this year.

The results clearly show that the efforts of the respective alien clearing teams are paying off. The alien vegetation is being slowly cleared and the fynbos has a greater chance to thrive.

A personal reflection from Matthew: During my time as an intern with Friends of Tokai Park I’ve learned a lot. My prior experience was in the oceanography field and working with satellite imagery in that context. Here, working with land remote sensing, there seems to be more that can be done because there are more features to work with. Due to this, I had to learn many unfamiliar concepts at the start of each task. I enjoyed time in the field joining the hackathon and exploring Upper Tokai Park. I believe my skill set has increased and I’d like to do more of this kind of work in the future. When walking in the Cape Town mountains from now on, I’ll always notice those pesky invasive species.

This project would not have been possible without funding from WESSA