Science-based ecological restoration crucial to survival of Cape's lowland fynbos

Reading Time: 9 minutes

By Zoë Chapman Poulsen, Alanna Rebelo and Tony Rebelo

Located at the southwestern tip of the African continent, the fynbos lowlands of the City of Cape Town are one of the most threatened habitats on Earth. They form part of South Africa’s Cape Floristic Region, classified as a World Heritage site for their extraordinary plant diversity.

According to research on the impacts of the urbanisation of Cape Town as a biodiversity hotspot, 13 plant species that once occurred in the greater Cape Town area are now extinct. A further 319 are listed as being of conservation concern on the Red List of South African Plants.

The Tokai-Cecilia Management Framework

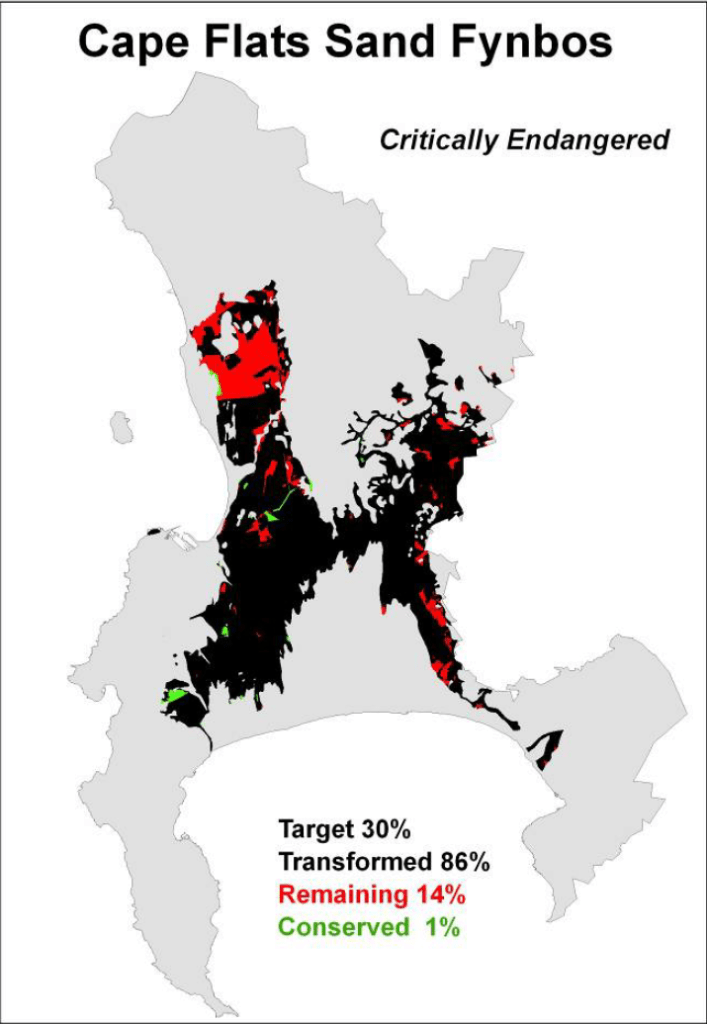

At the heart of Cape Town’s Southern Suburbs, Tokai Park is one of the city’s most popular lowland recreation spaces. Tokai Park, consisting of both lowlands and mountain slopes, is also home to two highly threatened vegetation types only found in the greater Cape Town area. These are Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, on the flats and Peninsula Granite Fynbos on the mountains, both listed as IUCN Critically Endangered Ecosystems.

Formerly a commercial pine plantation, some residents used to enjoy shaded walks on the lowlands. Others became increasingly excited by the species that started to reappear from the soil, once the shade of the pines disappeared, some of which are critically endangered, such as the Tokai Cape Flats Silkypuff (Diastella proteoides). After the exit of forestry from the Western Cape, the last pine trees are being harvested and the area is being restored to indigenous fynbos vegetation.

The Tokai Park area is now managed as part of the Table Mountain National Park (TMNP). The Tokai-Cecilia Management Framework is used as a guideline to inform management protocols and practices in the Tokai and Cecilia areas of the TMNP. Table Mountain National Park, which Tokai and Cecilia form part of, has an approved management plan.

One of the conditions of the framework is that the document is reviewed regularly, with the review open to a public participation process. A review of the current iteration of the framework is currently ongoing, with phase 2 to end on 11 December with a presentation of proposals developed by the public to SANParks’ CEO and Exco.

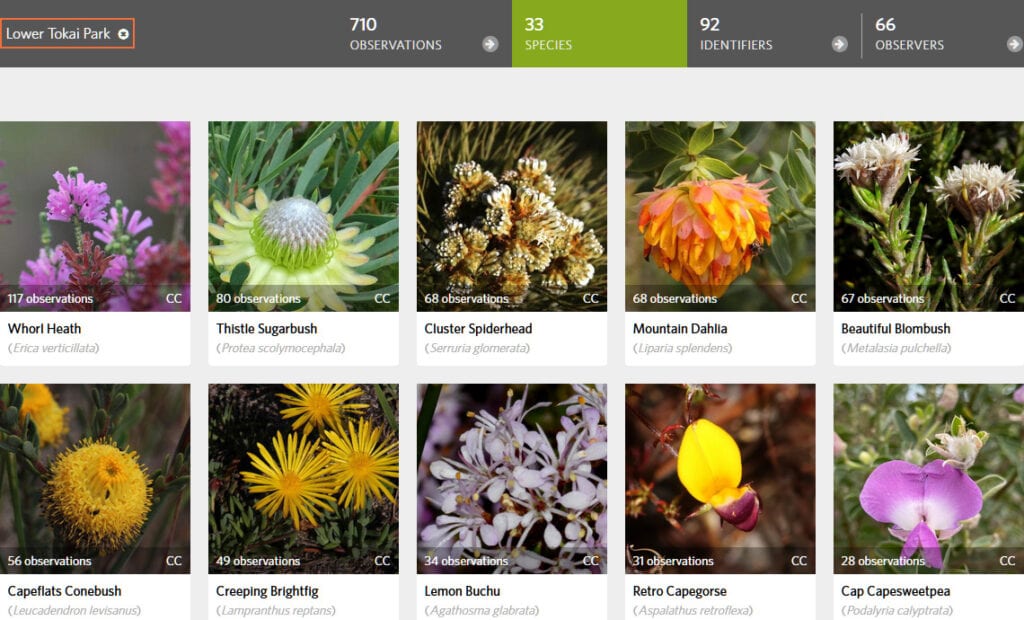

Tokai Park is the only continuous area of these unique habitats that survive that connect the Cape Flats lowlands with the mountain slopes of the TMNP, allowing movement of the animal components of the system. This biodiverse habitat is home to many highly imperilled species, such as the extinct-in-the-wild whorled heath (Erica verticillata) and MacDonald’s Heath (Erica turgida), for which establishing viable populations are essential.

The trouble with transitional planting

The concept of transitional planting was coined in the context of Tokai and Cecilia during the previous review of the Tokai-Cecilia Management Framework.

An idea was proposed that to achieve a compromise between user desire for shaded recreation and biodiversity conservation, pine trees would be initially felled and then restored to fynbos. After one fire cycle, new pine trees would be planted, grown and then harvested in the same space. The idea is that this would be a transitional process to fully restoring the area, i.e. after one further cycle of pines (about 30 years), the area would be ceded to restoration and there would be no more trees.

However, research into the impacts of pine tree overstorey on both the standing vegetation and the soil seed bank found that the longer there is a tree overstorey, the lower the species diversity of the soil seed bank.

This means that there is a reduction in restoration potential of the surviving soil seed banks at Tokai, the longer they are under a canopy of trees.

In addition, research has shown that the presence of pine plantations has an impact on small mammal diversity, an important bio-indicator of the effect of habitat alteration on faunal biodiversity. A further study found that pine plantations are like “inhospitable seas” around remnant native habitats within southwestern Cape forestry areas.

Planting of alien pine trees in a protected area is in contravention of South Africa’s National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004 (Nemba), so this initiative of transitional planting has not, to date, been implemented.

During the current review process of the Tokai-Cecilia Management Framework, suggestions have been made to replace the transitional plantings with areas of permanent plantings of trees indigenous to South Africa’s natural forest areas.

The Cape Flats is one of the least hospitable habitats for trees in the world, with trees being absent from its indigenous Cape Flats Sand Fynbos.

Research has also shown that historically there was no forest even at Upper Tokai Park, with Afrotemperate forest confined to a few small fire-protected gullies. With limited water resources to irrigate these trees during their establishment and their potential impact on the Cape Flats Aquifer, this is a plan that is likely to be highly costly and have social justice implications around water allocations.

With little water available, tree growth is likely to be stunted, as can be evidenced by the trees that have been planted by Friends of Tokai Park and SANParks along the perimeter of Lower Tokai Park, near Dennendal Road in 2011, which are struggling to grow. This is despite the existing pine plantations offering a “nursery environment”, or shade, something that foresters suggest would help transitional planted trees grow.

Save space for fynbos restoration: is compromise possible?

The Cape Flats Sand Fynbos and Peninsula Granite Fynbos of Tokai Park need all the space they can get for ecological restoration of these vegetation types. This is both to maintain ecosystem processes needed for viable systems, as well as maintain minimum viable populations of especially the threatened plant species. Activities that impact these will compromise the conservation of these systems.

With already too little of both vegetation types remaining to meet national and international conservation targets and space to allow species to adapt to climate change, there is no room for sacrificing these areas to non-environmentally friendly recreation options.

Both the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003 and the Table Mountain National Park management plan makes provision for “spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and tourism opportunities which are environmentally compatible” in national parks.

It is therefore critical that we select spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and tourism options that minimise negative environmental impacts, as well as options that offer the best social justice opportunities given the history of the Southern Suburbs.

The desire for shaded recreation

A key question to consider is whether recreational activities in the area are dependent on shade? We briefly reviewed the social media statistics of area usage within Table Mountain National Park. These statistics showed that the majority of Cape Town residents change their recreational behaviour to make use of the naturally cooler times of day.

Only a minority seem to seek artificial shade during the peak daytime temperatures. Therefore, is it necessary to compromise biodiversity conservation at Tokai Park for a minority who seek shaded recreation in the middle of the day?

One reason that Tokai Park gets additional attention is that it is flat (on the lowlands), compared to the majority of TMNP which is highly mountainous. Lower Tokai is one of the only continuous, natural flat sites as part of TMNP in the Southern Peninsula. Not everyone can or wants to walk up and down mountains.

Along with the biodiversity loss of the lowlands, we have also lost sites for recreational diversity. That said, there are still many greenbelts (10 adjacent to and connected to Tokai Park, amounting to over 19km of trails) and various city parks which are also flat, and contain extensive shaded areas.

Therefore, a critical question could be how we can increase the recreational diversity of landscapes in the wider area, to allow for diverse land types (shade area/non-shade) in flat areas. There is no reason why this recreational diversity should be required to be contained within a core conservation area at Tokai Park.

The importance of nature for health and wellbeing

South Africa is listed as one of the most psychologically stressed nations on Earth. There is clear evidence that psychological wellbeing correlates with experience of nature. This supports the retention of natural, as opposed to artificially produced and maintained outdoor areas, and highlights the uniqueness of natural parks in achieving this.

“Nature connectedness” (or “interconnection within nature”) has now been incorporated at the centre of the education framework for the Planetary Health Alliance (PHA). The PHA is a consortium of over 240 universities, non-governmental organisations, research institutes, and government entities from around the world committed to understanding and addressing global environmental change and its health impacts.

There is growing cross-sectoral recognition of how healthy nature equates to healthy people. Protecting the lowland fynbos species that face extinction is also a way we can honour future generations, as well as acknowledge our pre-colonial history.

People have different motivations, values and agendas, and therefore we should let science guide our actions when it comes to saving our biodiversity. A science-based approach informing the implementation of effective ecological restoration is the only way forward if we want to flatten the curve on species extinctions in South Africa.

Protecting nature is the best way we can care for the people of South Africa, both now, and in the future. DM

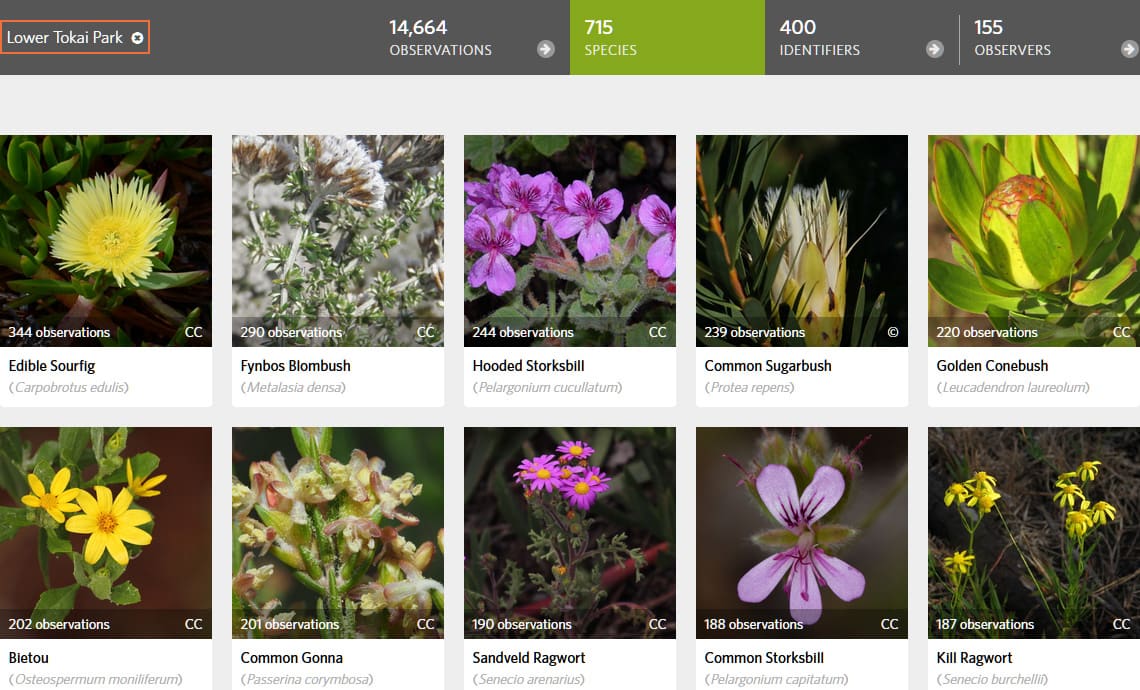

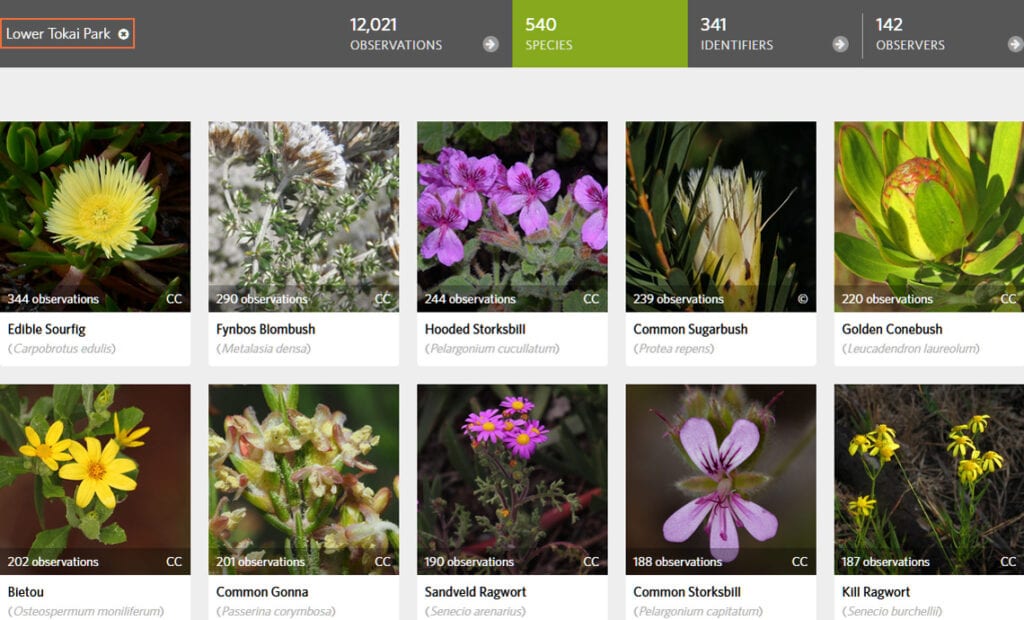

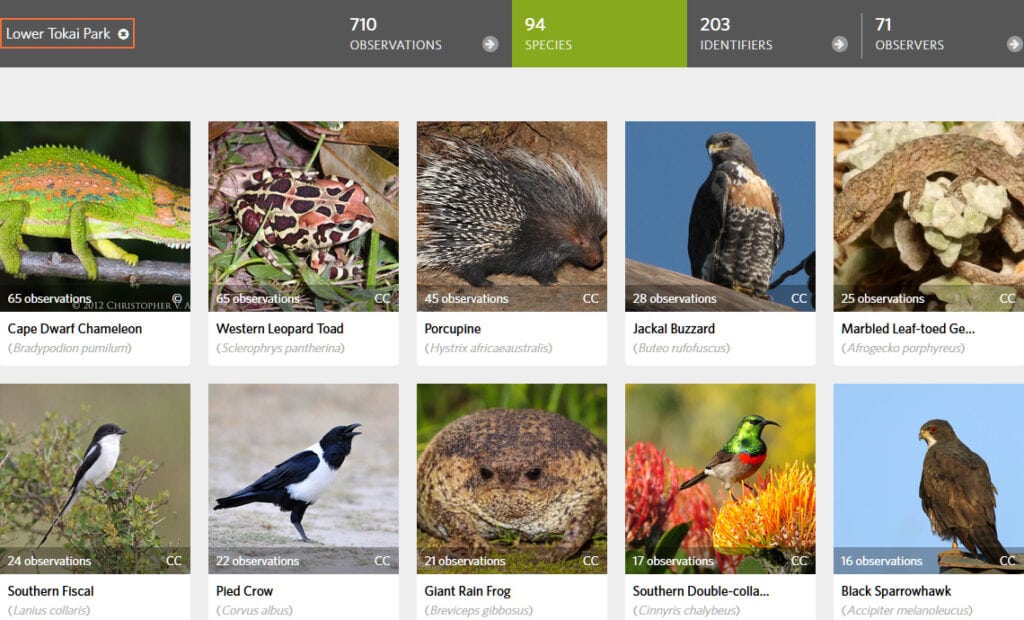

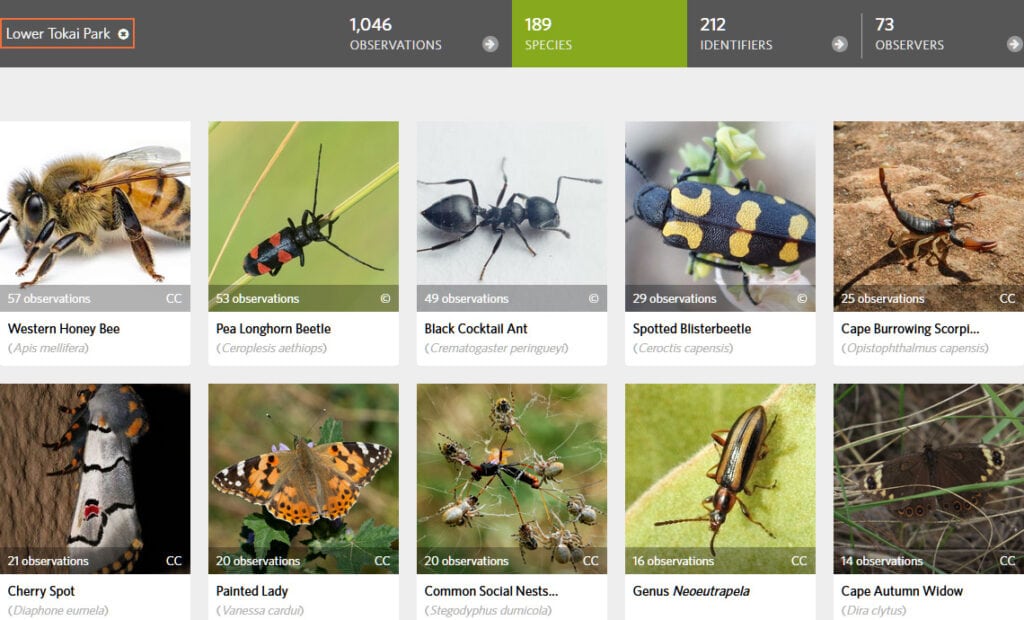

Species at Lower Tokai Park

Lower Tokai Park covers just over 100ha but has over 700 species of plants and approximately 550 species of indigenous plant.

By comparison, Augrabies Falls National Park is home to approximately 70 species of grass, shrubs, herbs and trees. A list of 625 plant species has been compiled for the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park (Management Plan: p19), 680 plant species are listed in the Mountain Zebra National Park (Management Plan p18), 780 in the Tankwa Karoo National Park (Management Plan p14) and more than 600 species can be found in the Bontebok National Park (Management Plan p13).

Although comparisons like this are odious, they do highlight the significance of Lower Tokai Park’s Cape Flats Sand Fynbos compared to other National Parks with many vegetation types.

Note: Only one of these Parks mentions Red List Plant species in its Management Plan. The Bontebok National Park lists 1 Critically Endangered, 9 Endangered and 7 Vulnerable species.

By comparison, the Lower Tokai Park section of Table Mountain National Park lists 2 species as Extinct in the wild, 9 species as Critically Endangered, 4 as Endangered and 12 as Vulnerable (Purcell‘s list for Bergvliet: X 2; CR 7; EN 6; VU 14; NT 5).

To find out more about the fantastic restoration taking place at Tokai Park, please click on the story boxes below:

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos

Peninsula Granite Fynbos

Zoë Chapman Poulsen is affiliated with the University of Cape Town; Dr Alanna Rebelo is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Conservation Ecology & Entomology at Stellenbosch University; Prof Tony Rebelo is affiliated with the South African National Biodiversity Institute and the University of Cape Town.

This project would not be possible without funding from the Izele Grant