We are losing biodiversity at an unprecedented rate. What is causing this devastation in the Western Cape and how do we stop and reverse a process that threatens the global web of life?

Mike Golby

It is now widely recognized that synergies between climate change and biodiversity conservation mean that the two agendas must be pursued concurrently to meet societal and environmental goals, such as the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals, Convention on Biological Diversity's Aichi Targets, and the Paris Agreement. This recognition is now also reflected in global social movements aimed at driving political action.

If you’re a layperson keen on learning something of conservation, you’ll have read a variation of the following five or six paragraphs so many times you’re probably able to recite your own version of them. Nonetheless, the information they contain bears repeating. So, here we go.

The Western Cape contains, mostly within its boundaries, the smallest of the world’s six plant kingdoms. The Cape Floral Kingdom, or Cape Floristic Region, covers less than 6% of South Africa’s surface and less than 0.5% of Africa’s. Yet, as home to some 20% of Africa’s flora, we host an extraordinarily diverse 9 000-plus vascular species in five biomes; Forest, Nama Karoo, Succulent Karoo, Thicket and Fynbos, the last of which has always been, by far, the largest.

Some 6 200 or 69% of these species are endemic, i.e. they grow nowhere else.

The Cape Floristic Region follows and lies west and south of the L-shaped Cape Fold Belt (CFB) mountains. All to the north, from the Northern Cape to the fringes of the Mediterranean Sea, across the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, South East Asia and the Indo Pacific, is taken up by our neighbouring Palaeotropical Plant Kingdom.

In an area less than that covered by the second-smallest state in Australia, Victoria (which falls into the Australian Plant Kingdom), we in the Western Cape host – by area – the most biodiverse plant kingdom on Earth.

Our proteoids, ericoids, restioids, geophytes and renosterveld are divided into many dozens of types generally based on or, more accurately, constrained by climate, topography and soil type – meaning each vegetation type, for example, Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, is made up of hundreds of species all of which are crammed into incredibly rich but small habitats.

And this amazingly bounteous and biodiverse plant kingdom does not exist in isolation. It’s part of an equally rich gene pool making up, with fauna, fungi, bacteria and other life forms, the ecologies on which all life depends. Without this ecological biodiversity, the constituents and ecological webs of life as we know it would unravel, collapse and die off – extremely swiftly.

Perhaps many of us take these facts for granted, but I still get a kick out of them. Look at it this way. Were we Capetonians to be transported back 5 000 years with no means of leaving what is undoubtedly one of the world’s most beautiful locales, we’d be surrounded by all the life and variety we need to sustain ourselves – and much, much more.

Okay, we’d be sharing the place with hippo, lion and other creatures that make weird and disturbing noises at night but, no matter how you view it, we’d still be living in Paradise. We’d be blissfully unaware that, just across yonder blue mountains, the Northern Cape holds its own allure. Cape Town would be the world, the world would provide and life would be good.

Thing is, we don’t live 5 000 years, or even 500 years, ago. We live today. And, if we look at any maps on the provincial government’s CapeFarmMapper or SANBI’s BGIS 2014 land cover map, we can literally see our biodiversity disappearing before our eyes.

Biodiversity in Crisis

We are destroying what little remains of our uniquely biodiverse Fynbos Biome through our:

• introduction of invasive alien species to the Wildland Urban Interface

• pollution of water, land and/or air

• disruption of species dynamics through the decimation of pollinators or dispersers – including long-tongued flies, butterflies and hopliine (scarab or monkey) beetles

• giving some species competitive advantage over others

• abuse and misuse of fire

• harvesting of Fynbos in the formal and informal cut-flower, medicinal and agricultural industries

• aggravation of damage caused by droughts and floods – by way of cutting paths and clearings, informal land transformation and indulging destructive leisure activities

• inadequate response to climate change, and…

• development of infrastructure, crop cultivation, forestry plantations and mines.

A little more than a century or two ago (a nanosecond, or no time at all, in geological time), Fynbos covered the Western Cape. Coexisting with other biomes, it was all over the place. Today, it has (and this is no overstatement) all but disappeared – thereby making its restoration and conservation, in what some fondly refer to as “the progressive Anthropocene”, our greatest and most pressing need.

That’s putting it politely. Even without the benefit of maps where we can see, quite clearly, our rapidly-burgeoning, increasingly urban population supported by agricultural and mining sectors taking up way more space than we do (a global phenomenon), is what’s known as a wicked problem.

It’s not just that our towns and cities have led us to pave over our Fynbos. Bringing food and goods to our people has led us to slice, dice and crisscross the Western Cape with our transport networks (road, and rail) to such an extent that no Fynbos habitat has been left untouched. Most (and, yes, that means most) of it is now covered or obliterated by highly-cultivated commercial farmlands and, with an ever-increasing population fed by an agribusiness economy driven by increasing growth and profit.

Announcing its plans for our national future, the Department of Agriculture told us in 2007:

Land used for agriculture comprises 81% of the country’s total area, while natural areas account for about 9%. Approximately 83% of agricultural land in South Africa is used for grazing, while 17% is cultivated for cash crops. Forestry comprises less than 2% of the land and approximately 12% is reserved for conservation purposes.

It’s worse in the Western Cape. In 2013, a provincial government report, Western Cape Provincial Profile: Emphasis on agricultural sector, put figures to our province. Of the 12.94 million hectares making up the province, 11.56 million hectares (or 89.3% of the land) is farmland, used chiefly for grazing.

And just 5.6% of the province is earmarked for “nature conservation”.

If these figures speak to our land-use priorities, our uniquely biodiverse plant kingdom has no chance of a sustainable future. Not by chance, the Cape Floristic Region is also a biodiversity hotspot for animal life. The pollution, chemical nutrients and pesticides, as well as the mismanagement of our hydrological resources resulting from our habit of feeding ourselves by way of an economy predicated on infinite growth and endless consumption, is literally killing life on Earth.

We are destroying the floral and faunal biodiversity that sustains us.

To say nothing of our increasingly-evident global Climate Crisis.

This leads me to another point and it’s a point vital to understanding what we at Friends of Tokai Park think we’re doing when you see us hacking away at alien invasives on the slopes of the Constantiaberg.

Do we believe David Wallace-Wells’s New York Post article, The Uninhabitable Earth, to be over the top? No. Do we feel Nathaniel Rich, in his 35 000-word New York Times article, Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change, is overly pessimistic? No.

Do we feel Johathan Frantzen deserves a roasting for his New Yorker article, What If We Stopped Pretending? No. Has Bill McKibben overplayed his hand by asking, “Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?” No. Do we believe Steffen et al to be incorrect in asserting in their “Hothouse Earth” paper, Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, that we might cross thresholds resulting in runaway climate change? Again, no.

The science and consensus on the science of climate change are not up for debate. The facts are in and the predictions are anything but optimistic. Our children know as much.

We are biodiversity at war with itself.

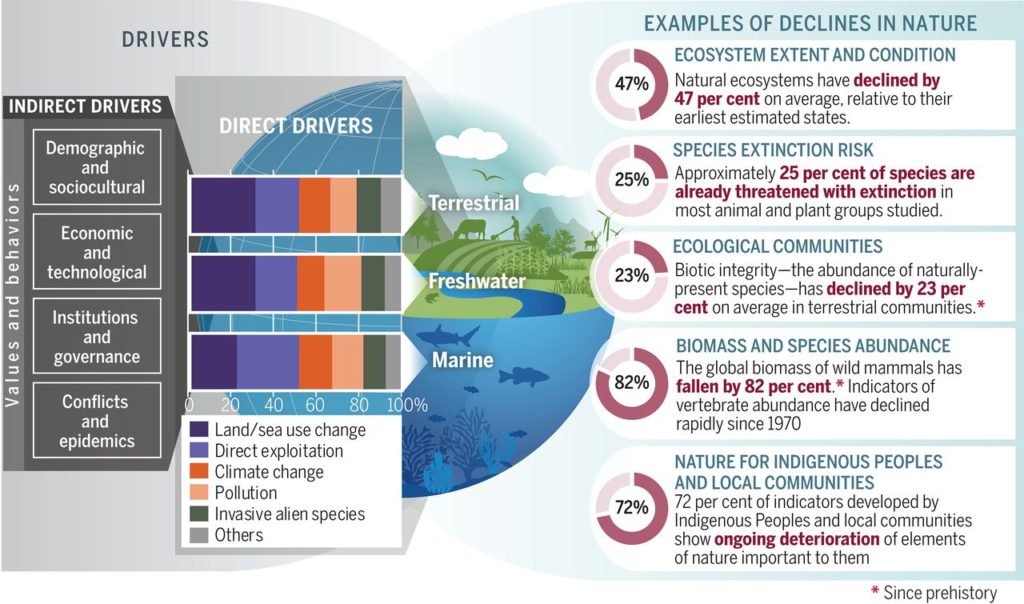

We are more than aware of (and clued up on) the real and immediate existential threat posed by the climate emergency. In fact, any meaningful consideration of biodiversity and the points in the above bulleted list should tell us that climate change is merely one of the problems we’ve brought on ourselves and all other species through our delinquent behaviour – extremely well illustrated in the following diagram accompanying the recent IPBES report, Summary for Policymakers of the IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

The above graphic (with human Values and behaviors to the left degrading and destroying Terrestrial, Freshwater and Marine ecosystems as elucidated to the right) articulates, in scientific terms, the assertion illustrated by Eric Nathan’s iconic image at the beginning of this article: “Yes, the destruction of our ecosystems and biodiversity is all our fault.”

Nevertheless, knowing this to be so, we must ask ourselves the question, “Why are we in the Western Cape losing biodiversity at a faster rate than other provinces and, indeed, countries or continents?” Part of the answer is to be found in the small habitat spaces afforded Fynbos species in the Mediterranean latitudes south and west of the Cape Fold Belt.

So, besides calling for the transformation of our economies, no more “business as usual” and the like, how do we preserve what little is left?

We can continue to fight the good fight – actively and passively.

If it is not hypocritical for us to worry about the loss of the Amazon, or the destruction of coral reefs, or the loss of biodiversity due to our fetish for palm oil in Indonesia, it is perhaps misguided for us to expend our energies doing so. We South Africans are not only major polluters of the air. We are by far the worst offender in the world when it comes to destroying our necessary biodiversity – if only because we have so much of it on our doorstep.

Our work is needed far closer to home.

So, what can we as Capetonians do to slow the Sixth Mass Extinction? Ultimately, we need to decide how far we’re prepared to go in restoring and protecting our biodiversity. Fortunately, there are two ways open to us to fight for nature and a sustainable, albeit very different, future to the one we might have envisioned a few decades ago.

The first is by way of on-the-ground work and activism and the second is by lobbying for the immediate, high-level uptake of this message in development planning. We can become active in policing activities that negatively affect our natural vegetation by reviewing Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), registering as interested and affected parties in nearby developments affecting natural areas, and by lobbying our local City councillors (beasts of a notoriously political stripe) for conservation action.

We can also involve ourselves in citizen science by way of monitoring. Anybody interested in finding, saving, and monitoring plant species can join the Custodians of Rare and Endangered Wildflowers (CREW), download the iNaturalist app and start logging species, or join a local nature society, for example, a WESSA-affiliated Friends group such as ours, the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa (WESSA) or the Botanical Society of South Africa.

If you’re involved with development planning in and around the City of Cape Town, encourage the densification of the city – to reduce its land footprint. Promote the densification of its hubs and the restoration of nature on the periphery. Force the reduction of air pollution by arguing the need for better transport infrastructure (such as trains that work). Promote water recycling within the city to decrease the burden placed on our aquatic ecosystems. Insist that we stop destroying our mountain ecosystems by draining them with unmonitored borehole extraction. And, for Heaven’s sake, ensure that waste is processed in accordance with set standards before dumping raw sewage into the ocean.

We have very little time. We need to initiate drastic fundamental change on a global scale. And such change starts with each of us. In our backyard. And, in our case, that means restoring biodiversity to Tokai Park. Because, without biodiversity, our Universe would be an indifferent place indeed.

Further reading

- CapeNature Western Cape Biodiversity Spatial Plan Framework 2017 Stellenbosch 2017

- City of Cape Town CCT Biodiversity Report: Celebrating a decade of biodiversity management 2008-2018 2018

- City of Cape Town City of Cape Town Nature Reserves: A network of amazing biodiversity 2010

- City of Cape Town The Cape Town Bioregional Plan (Policy Number 44854) 19 August 2015

- City of Cape Town Towards Achieving Biodiversity Targets for a Global Urban Biodiversity Hotspot: The City of Cape Town’s Biodiversity Network Oelofse G 2005

- Department of Environmental Affairs National Protected Area Expansion Strategy for South Africa 2016 DEA 2016

- Diaz S et al Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change Science 366 Issue 6471 December 2019

- IPBES Summary for Policymakers of the IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 2019

- Roberts CM, O’Leary BC and Hawkins JP Climate change mitigation and nature conservation both require higher protected area targets 375 Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B

- SANBI National Biodiversity Assessment 2018: The Status of South Africa’s Ecosystems and Biodiversity Synthesis Report 2019